Exploring Motio Functional Report Metrics – Blind Outcome Evaluations

Building upon one of our previous blog posts, the Motio Functional Report contains distinct sections, including daily activity highlights, an overall activity summary, blind outcome evaluations, and detailed activity graphs.

We presented before the importance of the Daily Steps and how to understand the Daily Activity Highlights. Today, let’s take a look at the Blind Outcome Evaluations section.

Blind Outcome Evaluations: what do they mean?

The Motio StepWatch System can perform three different blind evaluations during the acquisition period, based on three outcome measures validated in the lower limb prosthetic user population:

Two-minute of continuous walk (based on Two-Minute Walk Test – 2MWT)

Six-minute of continuous walk (based on Six-Minute Walk Test – 6MWT)

10-meters of continuous walk (based on 10-Meter Walk Test – 10MWT)

In previous research conducted by Stepien et al [1] and Godfrey et al. [2], most participants who used lower limb prostheses misreported their levels of low, medium, and high activity in comparison to objective assessments without any bias towards over- or underreporting.

The advantage of blind evaluations is that they capture the most accurate and unbiased representation of a patient's functional level. By removing the awareness of being tested, the results are less influenced by external factors and provide a more objective assessment of the patient's capabilities. However, in these blind evaluations, the environment is not controlled, unlike the validated outcome measures.

The different blind outcome evaluations presented in the Motio Functional Report show:

Mean and standard deviation: allow for an understanding of what the prosthetic user normally achieves in their day-to-day life.

Number of occurrences: allow the clinicians to understand the potential and how often the prosthetic user can achieve two minutes, six minutes, or 10 meters of continuous walking during the acquisition period.

Two-Minute Continuous Walk (2MCW)

The 2-minute continuous walk is an evaluation based on the 2MWT, where individuals walk a maximum distance in 2 minutes.

Figure 1 - Example of 2MCW blind test representation on Motio Functional Report.

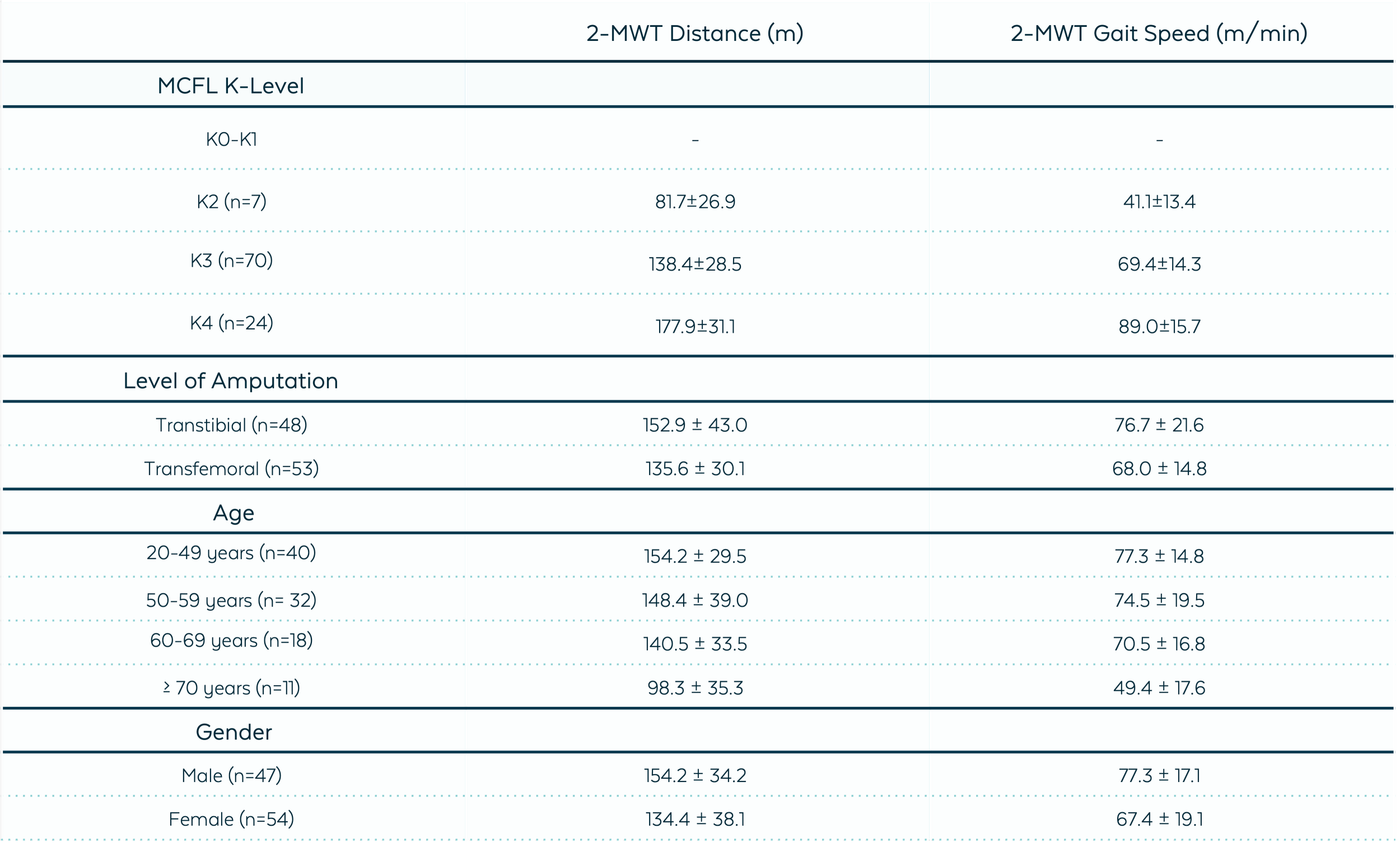

The reference values for the 2MWT, as determined by K-Level, can be seen in Table 1. Once again, because these numbers are not the results of blind tests, patients’ results may vary from the reference.

To ensure that the patient has had a "real" change in their functional status, a least detectable change distance of 34.3m (112 feet) on the 2MWT has been determined in unilateral transtibial and transfemoral prosthesis users[3].

Other reference values were found in the same study conducted by Gaunard et al [4]:

Table 1 - 2MWT reference values [4].

Six-Minute Continuous Walk (6MCW)

The 6-minute continuous walk is an evaluation based on the 6MWT, where individuals walk a maximum distance in 6 minutes, and it’s commonly used to compare changes in performance capacity.

Figure 2 - Example of 6MCW representation on the Motio Functional Report.

Even though this blind evaluation does not consider the environment, the reference values of the 6MWT are presented in Table 2 to help understand the outcome of this test, even though your patients' numbers may vary from the reference.

Table 2 - 6MWT Reference Values.

For the 6MWT, an increase in the distance walked indicates improvement in basic mobility. A minimal detectable change distance of 45m (148 feet) has been identified in unilateral transtibial and transfemoral prosthetic users, to be sure that the patient has undergone a “real” change in their functional condition [3], [7].

When to use 2MWT and 6MWT?

On research conducted by Reid et al [8], researchers found that the 2-min walk test strongly predicts the 6-min walk test. However, the research also discovered statistically significant between-group differences in 6MWT distances based on amputation etiology, K-level, and age. The mean K-level 1 and 2 participants (limited community ambulator) did not achieve the 300m threshold for community ambulation in the 6MWT, whereas participants considered as fully functional community ambulators (K-levels 3 and 4) were able to walk more than 300 m. This demonstrates that the 2MWT can be used as a measure of gait speed, and aerobic capacity in patients who are unable to complete a 6-minute walk test.

10-Meter Continuous Walk (10MCW)

The 10-Meter Continuous Walk is an evaluation based on the 10MWT, a performance-based measure that can be administered to assess gait speed in meters per second over a short distance.

Figure 3 - Example of the 10MCW test representation on the Motio Functional Report.

The 10MWT is normally performed in a clear pathway at least 10 meters long, with lines on the floor indicating the start, finish, and 2-meter marks from each end. The clinician should instruct the patient to walk at a self-selected speed and/or at a fast speed. However, in some cases [9], the reference values were obtained with patients walking a total of 12m indoors on a flat surface, with the middle 10m timed to allow for acceleration and deceleration.

With the Motio StepWatch System, the result presented on the 10MCW does not take into account any acceleration or deacceleration; it is done without the patient realizing it, and the value displayed on the report represents exactly 10 meters of continuous walking.

The 10MWT reference values are presented in Table 3 to help understand the outcome of this test, even though your patients' numbers may vary from the reference.

Table 3 - Reference Values OF 10MWT.

A Complete Approach to Prosthetic Rehabilitation

The Motio Functional Report, driven by the Motio StepWatch System, empowers rehabilitation teams to make well-informed decisions. By comprehensively analyzing the different sections, clinicians gain a vivid picture of each individual's daily activities and potential. This not only aids in setting realistic goals for rehabilitation but also contributes to the overall enhancement of the quality of life for prosthetic users. In the absence of specific activity recommendations for lower limb prosthetic users in current guidelines, the Motio Functional Report emerges as a valuable tool for personalized and effective prosthetic rehabilitation.

References

[1] J. M. Stepien, S. Cavenett, L. Taylor, and M. Crotty, “Activity Levels Among Lower-Limb Amputees: Self-Report Versus Step Activity Monitor,” Arch Phys Med Rehabil, vol. 88, no. 7, pp. 896–900, Jul. 2007, doi: 10.1016/J.APMR.2007.03.016.

[2] B. Godfrey, C. Duncan, and T. Rosenbaum-Chou, “Comparison of Self-Reported vs Objective Measures of Long-Term Community Ambulation in Lower Limb Prosthesis Users,” Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl, vol. 4, no. 3, p. 100220, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1016/J.ARRCT.2022.100220.

[3] L. Resnik and M. Borgia, “Reliability of Outcome Measures for People With Lower-Limb Amputations: Distinguishing True Change From Statistical Error,” 2011, Accessed: Apr. 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/91/4/555/2735043

[4] I. Gaunaurd et al., “The Utility of the 2-Minute Walk Test as a Measure of Mobility in People With Lower Limb Amputation,” Arch Phys Med Rehabil, vol. 101, no. 7, pp. 1183–1189, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.03.007.

[5] R. S. Gailey et al., “The Amputee Mobility Predictor: An instrument to assess determinants of the lower-limb amputee’s ability to ambulate,” Arch Phys Med Rehabil, vol. 83, no. 5, pp. 613–627, May 2002, doi: 10.1053/ampr.2002.32309.

[6] J. M. Sions, E. H. Beisheim, T. J. Manal, S. C. Smith, J. R. Horne, and F. B. Sarlo, “Differences in Physical Performance Measures among Patients with Unilateral Lower-Limb Amputations Classified as Functional Level K3 versus K4”, doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.12.033.

[7] A. A. Linberg et al., “Comparison of 6-minute walk test performance between male Active Duty soldiers and servicemembers with and without traumatic lowerlimb loss,” J Rehabil Res Dev, vol. 50, no. 7, pp. 931–940, 2013, doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2012.05.0098.

[8] L. Reid, P. Thomson, M. Besemann, and N. Dudek, “Going places: Does the two-minute walk test predict the six-minute walk test in lower extremity amputees?,” J Rehabil Med, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 256–261, Mar. 2015, doi: 10.2340/16501977-1916.

[9] H. R. Batten, S. M. McPhail, A. M. Mandrusiak, P. N. Varghese, and S. S. Kuys, “Gait speed as an indicator of prosthetic walking potential following lower limb amputation,” Prosthet Orthot Int, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 196–203, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.1177/0309364618792723/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0309364618792723-FIG2.JPEG.

[10] E. Russell Esposito, D. J. Stinner, J. R. Fergason, and J. M. Wilken, “Gait biomechanics following lower extremity trauma: Amputation vs. reconstruction,” Gait Posture, vol. 54, pp. 167–173, May 2017, doi: 10.1016/J.GAITPOST.2017.02.016.

[11] A. M. Boonstra, V. Fidler, and W. H. Eisma, “Walking speed of normal subjects and amputees: Aspects of validity of gait analysis,” http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/03093649309164360, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 78–82, Aug. 1993, doi: 10.3109/03093649309164360.